I FINALLY UNDERSTAND GENDER!!! + Why Sapphic Love is Genderless

What gender means to me and why I changed my pronouns back

Note: This is my own personal gender journey, and is not meant to be representative of anyone else’s. I just wanted to share my story and would love to hear your own journeys/thoughts in the comments.

I came out as nonbinary and changed my pronouns to they/them in 2022 and changed them back to she/they in 2023.

I felt a lot of guilt for “detransitioning” after being so vocal about being nonbinary, and switching my pronouns back made me worry that I was delegitimizing the nonbinary identity, especially because I couldn’t articulate to myself or others why I wanted to go back.

I initially changed my pronouns at a time when womanhood began to wear on me, with constant objectification and dismissal on account of my gender (more notably felt through my role as a camp counselor, where kids and parents did not respect me as much as my male counterparts). I had been thinking about possibly being nonbinary for a while at this point, as I liked androgynous representation, felt extremely queer, and was growing sick of how I was treated as “she.” I began to introduce myself as they/she to see how it would feel, and being called “they” filled me with immense euphoria. I felt whole and human, seen as just a person, and decided to fully come out as nonbinary. Although I was still perceived as a girl and treated like a girl, being vocal about wanting to be referred to as they/them felt like a punch against gender norms and a way to stand up for myself, free myself from gender expectations, and be proud of my queerness.

This switch however became exhausting. Although it was a big deal, it felt like a bigger deal to everyone else than it was to me. I just wanted to exist, and the spotlight on this word made my existence feel shined upon in a way that I just wanted to hide in the dark. It also felt tiring to constantly have to out myself to people and then comfort them when they used the wrong pronouns. I also did not expect the dual discomfort of being misgendered as “she” and correctly gendered as “they,” a learning curve in which I completely lost which one I liked more.

The hardest part was being asked multiple times, “Are you not a girl anymore?” - a question I could not process, nonetheless answer, because I had no idea what being a girl or not being a girl entailed.

Working at an overnight camp this past summer confronted me with gender in a way I had escaped from while living in my queer bubble at college. Although our groups were coed, we were still split into gendered cabins at night, and I created very close bonds with the girls in my group and the other female counselors and their girls, bonds that were created due to the context of our gender. The “girls” cabin fostered relationships based on care, gentleness, and love - all attributes given to feminity, which are not inherent to women but tied to them socially.

Although I came out as nonbinary to some campers and they were aware of it, many did not comprehend it due to their age and lack of exposure to it. I got used to being called “she” and grouped in with the girls, and surprisingly it felt relieving to accept those words as they attached themselves to me. Slowly, “she/her” began to have connotations of love and friendship rather than objectification and condescension, and stopped being the bad word I used to see it as.

I wasn’t able to fully process what the pronouns and their switching meant for me until I read Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters. In this novel, Amy, a trans woman, detransitions back to a man and goes by Ames. This ends his relationship with Reese, another trans woman. Ames then impregnates a cis woman, Katrina, but feels that while he can be a parent, he cannot be a father. Reese’s greatest desire is to become a mother, so Ames introduces the idea of raising the child with all three of them involved.

Torrey Peters’ does an amazing job directly questioning and analyzing the role of gender in how it molds our society and affects the characters. When Ames comes out to Katrina about his transgender past and why he detransitioned, Katrina asks, “So you got sick of being trans?” and Ames responds, “I got sick of living as trans. I got to a point where I thought I didn’t need to put up with the bullshit of gender in order to satisfy my sense of self. I am trans, but I don’t need to do trans.”

This was when I realized how heavily gender controlled me. I thought that they/them would be freeing, but instead, it solidified gender and made it impossible to escape. Labeling any form of gender nonconformity was making my gender journey so complicated and heavy, and honestly, passing by as cis was just much easier than constantly needing to explain myself to others.

I remember my friend at camp once said “I have never met someone who is not a girl who refers to themselves as a girl so much.” In Detransition, Baby, Peters writes, “She knew that no matter how you self-identify ultimately, chances are that you succumb to becoming what the world treats you as.”

This was when I got my euphoric moment of finally being able to comprehend why I could not answer “Are you not a girl anymore?” - My entire life I have been so aware of womanhood by what comes with it - objectification, diminishment, oppression. Womanhood was a class that we were born into, and with it came how we were treated and expected to act. The giant pile of expectations given unto women represents not how they are inherently different due to biology, but due to their group status, amalgamated into a giant stereotyped label rather than seen as individuals. This group I can easily attach myself to and see how I am within it, because of how I have been raised into it and always assumed to be part of it.

This gigantic grouping of women makes it impossible for me to understand what it means to be a “girl” on an individual level, and therefore why I could not answer that. There is no way to individually label someone as a girl. “Girl” carries gendered stereotypes that no human fulfills, that every “girl” is so much more than.

Yet, I would forever be a girl. Unless I physically transitioned to be a passing man, I would not escape being perceived and treated as a girl, and therefore I could not understand how I could be asked that question because, of course, I was still a girl. Society would always see me as a girl. I cannot escape being seen as part of that class by changing my pronouns, and my experience at camp made me appreciate being within it. It allowed me to focus on the beauty of female bonds rather than the maltreatment of women from society.

In the end, I gave up on being nonbinary. It was too exhausting to attach such a weighted word to myself and much easier to just pass with how society expects me to. But with this, also came a complete repudiation of gender and its weight. I had to see how much power the construct of gender had over me to give it up. Now “she/her,” “she/they,” or whichever pronoun, is just a way to refer to me rather than being a gendered cage to put me in. The “giving in” to gender was truly a way for me to break out.

Another large aspect of why I began to embrace womanhood again was due to the sapphic relationship I formed with one of the counselors. Our whirlwind summer romance made me feel whole and cared for, and I felt more myself within my queer relationship than I ever had before.

I’ve always, and especially then, loved the word lesbian. Despite it referring to sexuality rather than gender, something about how it sounds and what it represents felt so much more fitting to who I was than nonbinary. I remember telling her about how I loved the nonbinary lesbian flag, and she was confused by that label because nonbinary was the absence of gender, and lesbian was exclusively for women. But to me, lesbian represented love rather than a gender-specific sexuality.

Part of my love for lesbianism made me feel like maybe I was a woman then, that maybe I did need the “she” to fully fit in, but our relationship was not beautiful due to it being two women, but due to the lack of gender in general.

In her book All About Love, Bell Hooks goes into depth about how female and male gender roles translate into relationships and impact the ability to love. She explores “the impact of the patriarchy, [and] how male domination of women and children stands in the way of love,” by creating a power dynamic of how a man or woman should give or receive it; Soceity’s push of masculinity tells men they should not yearn for love while simultaneously telling women that it should be their main desire, creating a power dynamic and a fulfillment-gap within relationships. In analyzing the media about love, Hooks notes, “Men writing about love always testify that they have received love. They speak from this position; it gives what they say authority. Women, more often than not, speak from a position of lack, of not having received the love we long for.”

I have never felt more like a “girl” than when in a heterosexual relationship. Although my straight relationships have never been dominating or toxic, the gender dichotomy was always present, and my role as the girl within the relationship was extremely felt.

But with my sapphic summer fling, it was my first time experiencing true genderlessness. I often joked about her being “butch” because I strived to be “butch;” To me, that word symbolized the strength and independence I so strongly wished I had. It felt like we both simultaneously embraced womanhood while rejecting its box, completely erasing any power dynamic. Our manipulation of gender roles combined with the lack of a heterosexual blueprint allowed it to be purely based on our connection and the present.

Sapphic is used to describe attraction between women, but our connection wasn’t solely based on gender. It was built on a feeling of mutual belonging, comfort, and compassion. While this makes it feel feminine, it is not because feminity is inherently more gentle and caring, but because that is attributed to it.

In season 1 of The L Word, Alice dates Lisa, who is a “male lesbian.” Lisa threw viewers for a loop and was allegedly written on as a “joke character,” due to the confusion of how he was a man but identified as a lesbian, a contradiction that did not make sense. This was difficult for Alice to wrap her head around too, who ended the relationship because he did “lesbian better than any lesbian I know” and all she wanted was straight sex.

I find this to be an example of how love is so strictly defined by gender when it comes to heterosexual relationships. It is diminished to being simple and not mutually reciprocative, not wholly fulfilling. Men are supposed to not want or care about true love, and women are supposed to desire it but never fully get the connection they want - the entire basis of the relationship is based on the two genders and how they must interact.

When I was talking to my friend about Lisa and if they were supposed to be trans, they said that he was a man that “really identified with sapphic love,” and I think this is an example of how sapphic is a type of love that should not be restricted to love. While it is based on feminine attributes that make it so wholesome and encapsulating, it is excluded only to women because society does not expand these traits past feminity. The strong association between care and compassion makes it difficult to normalize such traits to be shown through masculine love.

Lesbian love is built off of many stereotypes like “U-Hauling” where it must be very committal and fast, with both partners immediately and mutually falling for each other with all of their emotions unabashed and unafraid to show. Yet if somebody did this in a heterosexual relationship, they would be “coming on too strong” or “trying too hard.” Rom-coms and romance novels perpetuate the ideal of true love being untethered and full-force, yet punish people for using it. Only with women is it normalized, but everyone deserves to have such respect and commitment within their relationships.

The words lesbian and sapphic are often intertwined and made synonymous, but in her article, “What does it mean to be Sapphic?” Yasmine Hamou writes, “‘sapphic’ strives to conjure an experience more akin to an intention toward attraction — one oriented less to any specific gender identity and more to the fullness of a potential lovers' humanity.”

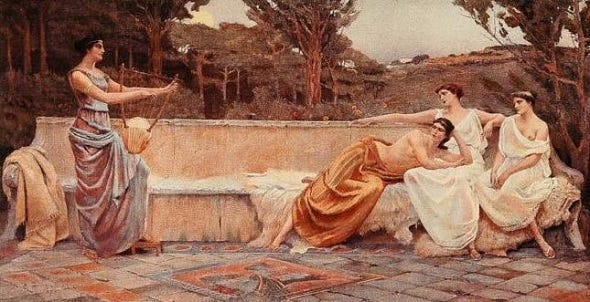

Sapphic love is named after the Greek poet Sappho who herself was not a strict lesbian. She lived on the Isle of Lesbos (where the word lesbian comes from), but she did not become a lesbian icon until the 20th century. Her poetry is known for her emotional expressions of love and desire, but the objects of her desire were not exclusively women. While she did write about her love and lust for women, she also extensively wrote about love for men and ended her life by jumping off a cliff due to her intense longing for the ferryman Phaon.

Her work was often taken in the context of how society wanted it to be - during her time, she was portrayed as a promiscuous heterosexual woman, and then through the ages, her narrative changed, whether it was ridiculing her for her homosexuality or using it as an abhorrent example of sexual deviance. When queer pride became to arise in the 20th century, she was then brought back into the zeitgeist but with a positive, iconic, and prideful twist.

So Sappho was not exclusively lesbian, and sapphic love is not only for women. It is for all cis, nonbinary, and trans people, and represents a “community where everyone has a mutual understanding of what it means to experience attraction, love, sexual desire, romance, community, friendship, companionship, inspiration and creativity through a similar lens, on our terms,” according to sex educator Katie Haan.

While sapphic love perhaps made me “reembrace womanhood,” due to the feminity attributed to it, it also made me understand a relationship free from the bounds of gender, as it represents a dynamic that can be between anyone and everyone - a world in which I could be anyone I wanted and love anyone I wanted, free from gender on both sides. Labels are often used to tie people to certain categories - while they can provide clarity and acknowledge the various identities and experiences people have, they can also simplify the complexities of who people are. Bisexual, lesbian, she/her, they/them, have all been words that have at times made me feel both so seen and so caged, but finally I have been able to know who I am rather than have to explain it, and imagine a way to be myself that must not be encapsulated by just one word.

References:

Book: hooks, bell. All About Love: New Visions. William Morrow, 2000.

Podcast: “Sappho: The Poet of Lesbos.” The Ancients, episode 181, 26 Feb. 2022.

Podcast: “Sappho” Stuff You Missed in History Class, 13 March. 2019.

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/sappho

https://www.them.us/story/what-does-sapphic-mean

https://dressingdykes.com/2021/03/19/depicting-sappho-the-creation-of-the-original-lesbian-look/